The Quiet Breach: What the Foreign Office Attack Reveals About UK Government Cybersecurity

Why it matters: The October 2024 breach of the UK Foreign Office – confirmed only on 19 December 2025 – exposed visa systems and tens of thousands of diplomatic files to suspected Chinese state-sponsored actors. The two-month gap between incident and public acknowledgment, combined with government characterisation of the attack as a “technical issue,” raises uncomfortable questions about breach disclosure standards that every UK organisation should examine.

The attack we weren’t told about

Trade Minister Chris Bryant confirmed the Foreign Office breach during parliamentary interviews on 19 December, describing an October 2024 intrusion that accessed diplomatic communications and visa processing systems. The government’s position: the breach was a “technical issue” that was “rapidly closed,” posing “low risk” to individuals whose data was accessed. [1][2]

The details tell a different story. Reporting indicates access to approximately 10,000 files, including sensitive diplomatic correspondence and visa application data. The breach reportedly affected systems handling communications between UK diplomats and foreign counterparts – precisely the kind of intelligence that hostile states prize. [3]

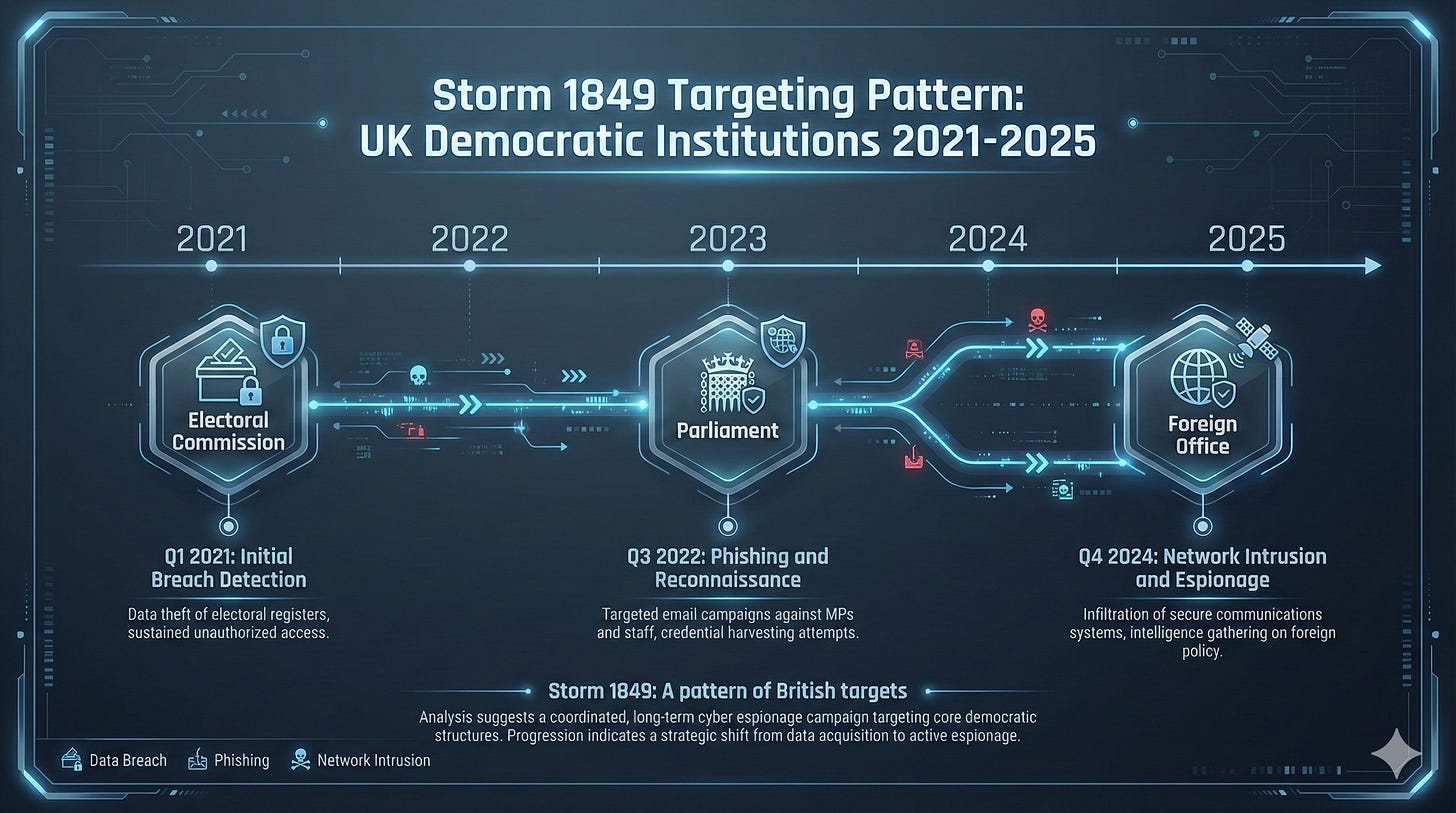

Attribution remains officially unconfirmed, but the suspected threat actor is Storm 1849, a China-aligned advanced persistent threat group. This attribution, while disputed by government, aligns with the group’s established pattern of targeting UK democratic institutions.

Storm 1849: A pattern of British targets

The Foreign Office breach does not exist in isolation. Storm 1849’s suspected involvement connects this incident to a documented campaign against UK institutions:

Electoral Commission (2021-2022): Attackers accessed the personal details of approximately 40 million UK voters over more than a year before detection. The National Cyber Security Centre assessed with high confidence that a China state-affiliated actor was responsible.

UK Parliamentarians (2024): Multiple MPs received alerts that their accounts had been targeted by the same threat actor, with spear-phishing campaigns exploiting Cisco ASA zero-day vulnerabilities in what researchers termed the “ArcaneDoor” campaign.

Foreign Office (October 2024): The latest confirmed target, with access to diplomatic systems and visa data.

This progression – voters, legislators, diplomats – suggests systematic intelligence gathering across British democratic and governmental infrastructure. The tradecraft remains consistent: exploitation of enterprise network equipment, credential harvesting, and extended dwell time within compromised environments. [1][4]

The pattern is clear: UK government systems have been systematically targeted by the same threat actor across multiple years, yet each incident has been treated as isolated rather than part of a sustained campaign.

The disclosure gap

For security professionals, the most troubling aspect may not be the breach itself but the timeline. The attack occurred in October 2024. Public confirmation came on 19 December 2025 – more than fourteen months later. During that period, individuals whose visa data was accessed had no opportunity to take protective action.

The government’s characterisation deserves scrutiny. Describing access to diplomatic communications and visa systems as a “technical issue” understates both the sophistication required and the intelligence value obtained. “Rapidly closed” provides no meaningful timeline. “Low risk to individuals” offers no explanation of how that assessment was made.

This matters beyond the Foreign Office because it establishes a template. If government can characterise state-sponsored access to sensitive diplomatic systems as a technical issue posing low risk, what standard applies to private sector breaches? What disclosure obligations actually mean in practice?

Analysis: What this reveals about UK cyber posture

Three observations emerge from examining this incident alongside the broader threat landscape.

First, attribution ambiguity serves political purposes. The government has not formally attributed the attack to China, despite threat intelligence strongly suggesting Storm 1849 involvement. This creates diplomatic flexibility but leaves UK organisations without clear guidance on nation-state threat prioritisation.

Second, disclosure standards remain inconsistent. The NCSC reported a 50% year-on-year increase in “highly significant” cyber incidents affecting essential services through August 2025. The Cyber Security and Resilience Bill, currently progressing through Parliament, will mandate 24-hour early warning and 72-hour detailed notification for essential services. Yet government’s own disclosure practices do not reflect these standards. [5]

Third, the targeting pattern demands strategic response. Storm 1849’s progression from electoral systems to parliamentary accounts to diplomatic infrastructure represents escalating access to UK decision-making. Defensive measures focused on individual incidents miss the campaign-level coordination.

Risks and constraints

Several factors complicate response.

Intelligence sensitivity: Full disclosure of breach details may compromise ongoing investigations or reveal detection capabilities. Government must balance transparency against operational security.

Diplomatic complexity: Formal attribution to China triggers diplomatic consequences. The calculation involves trade relationships, security cooperation, and broader geopolitical positioning.

Detection limitations: If Storm 1849 maintained access for an extended period before discovery – consistent with their tradecraft elsewhere – the scope of accessed material may be larger than currently acknowledged.

Supply chain exposure: The Foreign Office, like all government departments, relies on contractors and managed service providers. The breach pathway may involve third-party access, with implications for the broader government supply chain.

What to do next

For boards and executives: Request a briefing on nation-state threat exposure specific to your sector. If your organisation handles government contracts, visa processing, or diplomatic liaison, assume elevated targeting risk. Review your breach disclosure procedures against the standards the Cyber Security and Resilience Bill will impose – even if not yet law, they represent direction of travel.

For security leaders: Assess whether your threat model adequately weights state-sponsored actors. Review network segmentation between systems handling sensitive data and broader infrastructure. Examine dwell time detection capabilities – Storm 1849’s tradecraft involves extended presence before exfiltration.

For mid-market organisations: The Foreign Office breach demonstrates that even well-resourced government departments face sophisticated intrusion. Your organisation likely cannot match their defensive budget, but you can implement zero-trust architectures, enforce multi-factor authentication universally, and maintain asset inventories that enable rapid incident scoping.

The quiet breach is not just a government problem. It is a signal about the threat environment every UK organisation operates within.

Disclaimer: This article represents analysis based on publicly available information as of December 2025. It does not constitute legal, financial, or professional advice. Attribution assessments reflect reported intelligence community positions and remain subject to revision.

If your organisation needs support assessing nation-state threat exposure or developing incident response capabilities, Arkava helps mid-market enterprises build resilient security postures with measurable outcomes.