Gene-Edited Cells Offer New Hope for Type 1 Diabetes

For the first time, donor insulin-making cells survived and worked in a person with type 1 diabetes without anti-rejection drugs—a landmark step toward a functional cure.

Why it matters

A Swedish man with long-term type 1 diabetes is now making his own insulin after receiving donor cells that were gene-edited to hide from his immune system.

He needed no anti-rejection drugs, marking a genuine first in diabetes care

The first-in-human success

In late 2024, researchers at Uppsala University Hospital and biotech firm Sana Biotechnology transplanted insulin-producing islet cells—taken from a donor pancreas and precisely gene-edited—into a patient’s forearm muscle.

Unlike every previous transplant, he received no immunosuppressants.

Three months later, blood tests showed his body was making insulin again.

Scans confirmed the transplanted cells were still alive and functioning.

He continues to inject a small amount of insulin because doctors deliberately used a low “safety-first” dose, but the principle worked.

For the first time, transplanted islet cells survived and produced insulin without any immune-suppressing drugs.

This single patient proved something long thought impossible: donor islet cells can live and work without anti-rejection drugs.

A quick refresher: what goes wrong in type 1 diabetes

Type 1 diabetes happens when the body’s own immune system attacks the pancreas’s insulin-making beta cells. Without insulin, sugar stays in the blood, causing long-term organ damage.

People manage it with injections or insulin pumps—a daily balancing act that still leaves them vulnerable to low blood sugar, heart disease and other complications.

Globally, about 9.5 million people live with the condition, a number expected to reach 14.7 million by 2040.

How scientists made “invisible” insulin cells

Think of the immune system as nightclub bouncers checking ID badges. Donor cells normally wave badges saying “I’m a trouble-maker”, so the bouncers throw them out.

The researchers changed that in two clever steps:

They removed the ID badges.

Using the gene-editing tool CRISPR-Cas12b, they switched off two genes—B2M and CIITA—that make the identity markers the immune system recognises. Without them, the new cells look like they belong.

They added a “please don’t attack me” sign.

They boosted a protein called CD47, which sends a calm “do not eat me” signal to immune cells such as macrophages and natural killer cells.

Together, these tweaks create hypoimmune cells—cells that are “quiet” to the immune system. The approach tackles both kinds of rejection:

adaptive immunity (T cells that target foreign tissue)

innate immunity (cells that attack anything unfamiliar)

The results so far

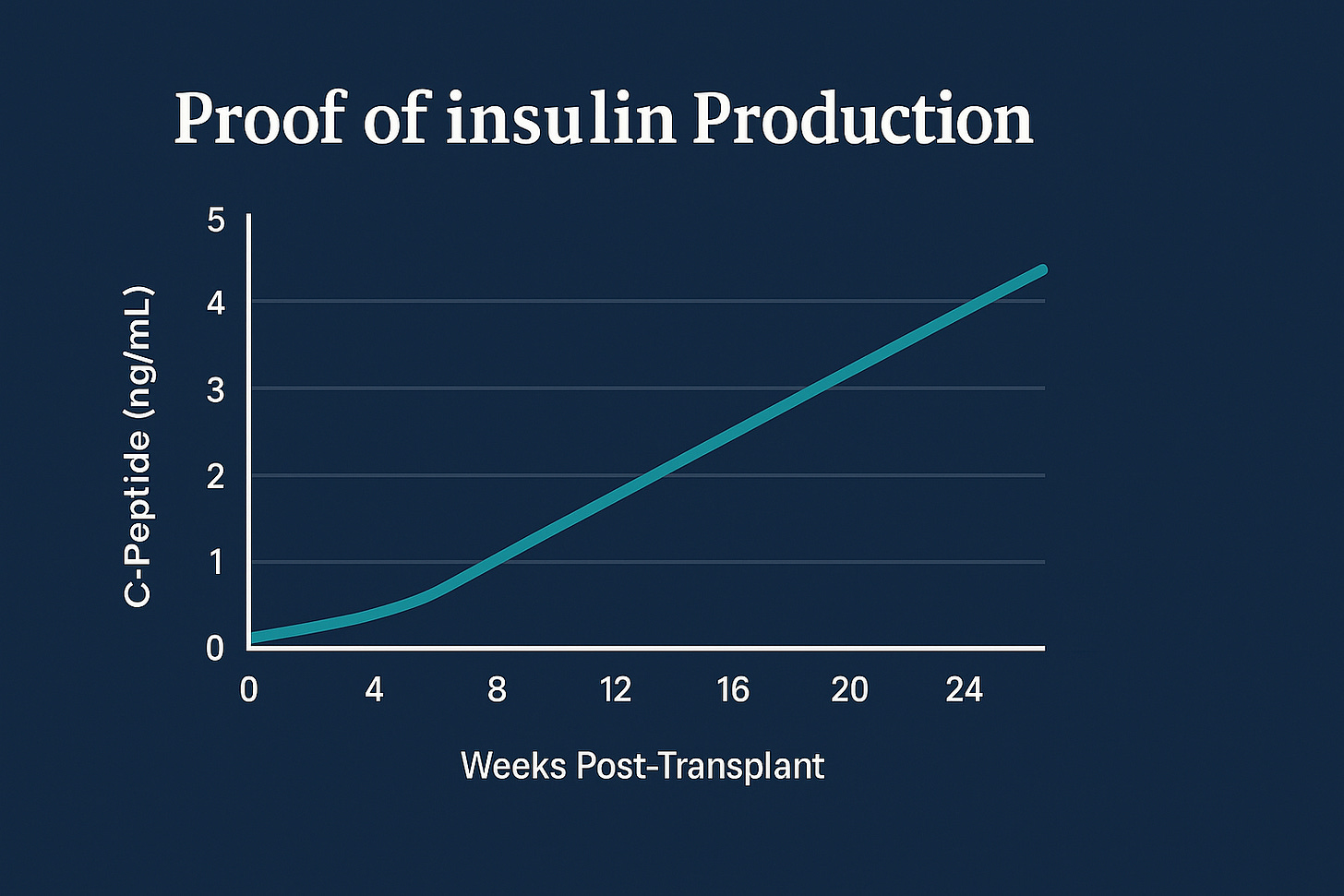

Insulin detected: The patient’s blood contained C-peptide, proof that the new cells made insulin.

No immune attack: Scans and lab tests found no signs of rejection.

No serious side effects: Only mild numbness and a small clot at the injection site were reported.

Still some insulin injections: Expected at this early, low-dose stage.

Why this is different

Traditional islet transplants can restore insulin production—but only with lifelong immunosuppressants that raise infection, cancer and kidney-damage risks.

Other methods try to encapsulate cells in tiny membranes or grow new ones from stem cells. These can help, but they bring new engineering problems and still rely on drugs or devices.

This new method engineers the cells themselves so that the body naturally tolerates them.

No drug cocktails, no implantable capsules—just stealth biology.

Next steps for researchers

Use full-strength doses to see if people can become completely insulin-independent.

Recruit more volunteers of different ages and immune profiles.

Track results for years to check lasting safety and stability.

Scale up manufacturing using lab-grown stem-cell islets (project SC451) to ensure steady supply

What this could mean for patients

If later trials confirm these results, people with type 1 diabetes might one day replace daily injections and alarms with a single outpatient transplant that restores natural insulin control—without drugs.

The NHS and other health systems would still need to weigh cost, manufacturing and regulatory hurdles, but the potential change in quality of life is enormous.

The cautious view

It’s vital to keep perspective:

This is one patient, followed for months, not years.

We don’t yet know if the protection lasts or if the immune system will adapt.

Larger studies are now underway.

But for a community that’s waited a century since insulin’s discovery, even a glimpse of drug-free insulin production feels revolutionary.

Science has moved the goalposts: a functional cure for type 1 diabetes is no longer theoretical.

Disclaimer

This article summarises peer-reviewed medical research published in 2025. It is not medical advice. People with diabetes should consult their healthcare professionals about treatment options.

The hypoimmune cell approach is elegant because it sidesteps the entire immunosuppressant drug market rather than competing with it, which creates an interesting dynamic for companies like Novo Nordisk whose insulin franchise still generates billions annually. If this scales, the real competive threat isn't just to insulin but to the entire glucose monitoring ecosystem that's become embedded in diabetes management. The stem cell manufacturing pipeline (project SC451) is critical, donor pancreases are finite and unpredictable which is why previous islet programs failed to scale despite clinical success. The one patient three month result is promising but type 1 is autoimmune, so the durability question is whether the edited cells can truly evade the same immune mechanisms that destroyed the original beta cells in the first place.